search the site

IN FOCUS: How a devastating oil spill has sparked new fears about Southeast Asia’s gas ‘feeding frenzy’

IN FOCUS: How a devastating oil spill has sparked new fears about Southeast Asia’s gas ‘feeding frenzy’

When oil tanker MT Princess Empress sank this January in the Philippines’ Verde Island Passage, spilling huge amounts of industrial oil into the sea, it prompted more calls from local communities, environmental groups and energy analysts to question what has become a regional rush to expand fossil fuel infrastructure.

Jack Board

21 Oct 2023 Channel News Asia

POLA, Philippines: It took just a couple of days for the calamity to arrive in Pola, for the black water to start lapping at the beaches of the quiet fishing community.

On Jan 28 this year, about seven kilometres offshore from the island province Oriental Mindoro, a tanker named MT Princess Empress had sunk in rough sea conditions.

ADVERTISEMENT

Its toxic cargo of 800,000 litres of industrial oil began spilling into one of the world’s most important biodiversity hotspots: the Verde Island Passage, a vital waterway separating the Luzon and Mindoro islands in the Philippines.

A nightmare was being realised.

Hazmat suits that had been used by community personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic suddenly had a new purpose – protecting locals from the sludge sweeping into the municipality’s cove.

“The oil was so sticky and had a very pungent smell. The sand soaked up most of the oil so our fisherfolk had to scoop it out. This is why many were admitted to the hospital in Pola,” local mayor Jennifer Cruz told CNA, explaining that many suffered from cramps, vomiting and dizziness after breathing in the toxins.

The disaster that would unfold – and that started a crisis that continues to this day – was emblematic of a greater fear that had increasingly grown among the scientific community, environmental groups and energy analysts.

Namely, that the environment, climate and local people’s livelihoods are being imperilled by a regional rush to further develop the fossil-fuel industry, especially in the form of liquefied natural gas (LNG) hubs and potentially, many more activated oil and gas fields.

“More and more tankers – LNG tankers – will be able to pass through the area,” said Mr Ivan Andres, the deputy head of research and policy from the Center for Energy, Ecology, and Development (CEED), a Philippine non-governmental organisation focused on sustainable energy, industry and governance.

“And of course, with the elevated number of these tankers in the area, there’s more chances of capsizing and catastrophic events such as the one we saw in Oriental Mindoro.”

Heavy shipping – and potentially dangerous cargoes – is one of the symptoms of the growth of that industry. So too is the leakage of heavy metals into waterways and heightened interest in the expansion of offshore oil and gas drilling.

In the Philippines, industrial activity centres on Batangas in southern Luzon, south of Manila, where infrastructure – in the form of new or renovated power stations and LNG terminals – is rapidly being brought online.

The MT Princess Empress had been traversing waters heavily used by tankers and cargo ships in and around Batangas. LNG tankers are increasingly part of that picture.

They are the same waters used for generations by small-scale fisherfolk from places like Pola, the community worst hit by the oil spill, to Naujan, the epicentre of the disaster response activities for the weeks and months that followed after the incident.

“These developments, starting from the oil spill, the fossil gas and LNG development in the area, as well as the plethora of issues being faced by the fisherfolk and coastal communities, are definitely a wake up call for greater protection and safeguarding of the Verde Island Passage,” Mr Andres said.

“The empirical data suggests that quality and the health of the Verde Island Passage is declining. It’s proof that the current policies and laws governing it are insufficient.”

STRAINING AN ALREADY VULNERABLE MARINE ECOSYSTEM

The Verde Island Passage is regarded as the centre of global shore-fish biodiversity and is estimated to support some two million people in terms of food and livelihoods. It is a fisheries hub, burgeoning e-tourism site and critical shipping pathway.

It forms part of the greater Coral Triangle, a vast ecosystem that stretches across the marine territories of the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Timor Leste, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. It is complex, delicate and ancient.

Its ecological and economic importance to many is why there is such concern about booming levels of industrial activity along coastlines that border the passage.

Batangas is currently home to five out of six fossil-gas power plants in the Philippines. There are plans for many more. Eight additional gas power plants are in the pipeline for the province and there are proposals for seven LNG terminals as well.

Dr Jayvee Saco, from the VIP Center for Oceanographic Research and Aquatic Life Sciences at Batangas State University, said he expects that such infrastructure will place great strain and risk on an already vulnerable marine ecosystem.

“Unfortunately with that hotspot for major transportation, it also threatens biodiversity. The marine ecosystem is interconnected. There are no specific boundaries,” he said.

“If this industry has a possible leakage there will be a long-lasting effect on the marine environment.”

CEED conducted a series of scientific tests focused on water quality and marine ecology in the areas of heavy industry around Batangas, before the oil spill occurred in 2022.

It found excessive concentrations of polluting metals, including phosphate, chromium, copper, lead, and zinc at levels that could be “detrimental to ecological health and human health due to bio-accumulation in commercially-important fish”.

Mercury, which has links to coal combustion, electrical power generation and industrial waste disposal, was also found at higher levels than in previous years.

“As it stands, we already see the impact of the existing power plants. We see the impact on coral cover due to siltation and development of industry, and we also see the impact on the declining fish supply,” Mr Andres said.

Earlier this year, the organisation filed a petition to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources over poor water quality affecting local communities in Ilijan, adjacent to the largest natural gas facility in the Philippines

So far, the government has not acted on the petition.

Indeed, instead of slowing down industrial developments in the area, the energy industry has been given a green light to expand its footprint.

RISING ENERGY DEMANDS, HIGH POWER BILLS

Since a moratorium on new coal plants was declared by the Philippine government in 2020, major energy sector players have shifted their focus and capital to gas instead.

It is a trend unfolding across Southeast Asia.

Energy demand remains on a strong growth path in the region and is expected to triple by 2050, compared to 2020.

While the proportion of fossil fuel is diminishing, it will still constitute most of the energy supply in Southeast Asia by 2050, where its share will only be down to 74 per cent from 84 per cent, according to the 7th ASEAN Energy Outlook.

As a result, a reliance on fossil fuels – and especially gas – should be anticipated, according to Mr Beni Suryadi, from the ASEAN Centre for Energy.

“Energy supply needs to be secured at every moment to allow our economy to function properly,” he told CNA.

“Since the ASEAN economy is built upon fossil fuels, investments in natural gas become unavoidable to secure a reliable energy supply.”

It is a theory fiercely contested by other energy analysts.

“What we’re seeing right now is a total feeding frenzy for natural gas in the region beyond what market fundamentals would dictate is necessary,” said Mr Sam Reynolds from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

Natural gas is being framed by industry and many governments as a “transition fuel” to help economies fill the supply gap as coal is replaced by renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar.

CEED estimates that 138GW of new gas-fired power plants and 118 LNG terminals are being proposed or already being built within the region. Vietnam is the leading developer of plant capacity, while Thailand has the most potential import terminal capacity in the pipeline.

The proportion of natural gas used in Singapore’s electricity generation – mostly piped from Indonesia and Malaysia – has risen from 19 per cent in 2000 to more than 90 per cent today.

It is also transitioning to become a leading trading hub for LNG in the region, as it has for petroleum in the past, given the finite natural sources available in its neighbours’ gasfields.

Natural gas is a reliable, baseload power source that suits existing power grids and traditional business models.

But not only is natural gas a carbon-emitter when being burnt or extracted, which contributes to climate change, it is also extremely expensive. Huge recent spikes in LNG prices have been caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and production cuts by Saudi Arabia.

The cost of taking such a route and developing more gas-powered plants will lock in high energy prices for the average power consumer across the region.

“In most countries in Southeast Asia, the costs of power and the costs of fuel are passed from the generation companies to the distribution utilities and then to the final consumers,” Mr Reynolds explained.

“The reality is that companies currently have no incentive to rely on cheaper fuels, because all of those costs are borne by consumers.”

The Philippines, as an example, already has among the highest prices for electricity in the entirety of Asia. In 2022, its household electricity prices were only lower than those in Japan and Singapore.

“Their vulnerability to global natural gas supply shocks may intensify as they are increasingly connected to the global LNG markets,” Mr Beni said.

Given the Philippines’ high exposure to climate change impacts – it was ranked the most disaster-prone country in the world last year by the World Risk Index – opponents say the government needs a smarter and cleaner strategy.

“It’s really ironic that the Philippine government is still peddling fossil fuel dependency. It’s mind-boggling to be precise. These are really rehashed myths and lies, but now it’s in the form of gas,” said Mr Gerry Arances, CEED’s executive director.

“What goes around comes around for the Philippines. It’s not just destruction and high costs of electricity. But it’s a near-term impact on climate disasters. And that’s a lived reality for Filipinos.”

PRESIDENTIAL APPROVAL

Regardless of the criticisms or the apparent risks, the Philippines Department of Energy (DOE) – and the Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos himself – is a keen supporter of the development of more gas infrastructure.

The president called on the country’s Congress, the national parliament, to help support the natural gas industry during his first State of the Nation Address in 2022.

Meanwhile, the DOE is sanctioning major projects from companies like San Miguel Global Power in Batangas, despite concerns that those assets could be stranded – basically losing their value or becoming unusable – in years to come.

Mr Rino Abad, the director of the department’s Oil Industry Management Bureau, said he does not see the strategy as risky, given what he calls “limited options” for the country.

“We need natural gas, not by any choice. But it’s probably our only choice,” he told CNA. “What’s the harm of getting into gas? It happens to be a good complement to renewables. It supports the baseload to replace coal.

“So, I think it’s a no-brainer for us to really get into natural gas, as long as other more economical, appropriate technologies come in later.”

A company like San Miguel Global Power, which is hugely influential and through a subsidiary now operates key gas infrastructure like the Ilijan Power Plant, has not added any renewable capacity to its portfolio since 2014.

Its fossil-fuel reliance raises major financial red flags, according to IEEFA and is completely incompatible with the company’s own 2050 net-zero target.

Mr Reynolds said natural gas does not meet the criteria as a transition fuel, as “it’s not affordable, it’s not sustainable and it’s simply not realistic for a country like the Philippines”.

“This idea that natural gas is the only available option is simply false. And the Philippines is a perfect example of why that’s false,” he said.

NEW GAS FRONTIERS

At the same time that gas demand is growing significantly in the Southeast Asian region, production is on the decline.

The Philippines’ existing major gas field – Malampaya – was commissioned back in 2001 and is expected to be depleted within five years. With domestic sources running dry, companies and governments are shifting to importing LNG instead to power their energy plants.

That leaves them exposed to the turbulence of global markets.

Economic opportunity and market risk is therefore driving heightened interest in offshore oil and gas exploration and extraction.

The global offshore oil and gas sector is set for the highest growth in a decade in the next two years, according to analysis by Rystad Energy, with US$214 billion of new project investments lined up.

Data from Global Energy Monitor’s Global Oil and Gas Extraction Tracker shows that 19 gas fields are up for approval in Southeast Asia by 2025.

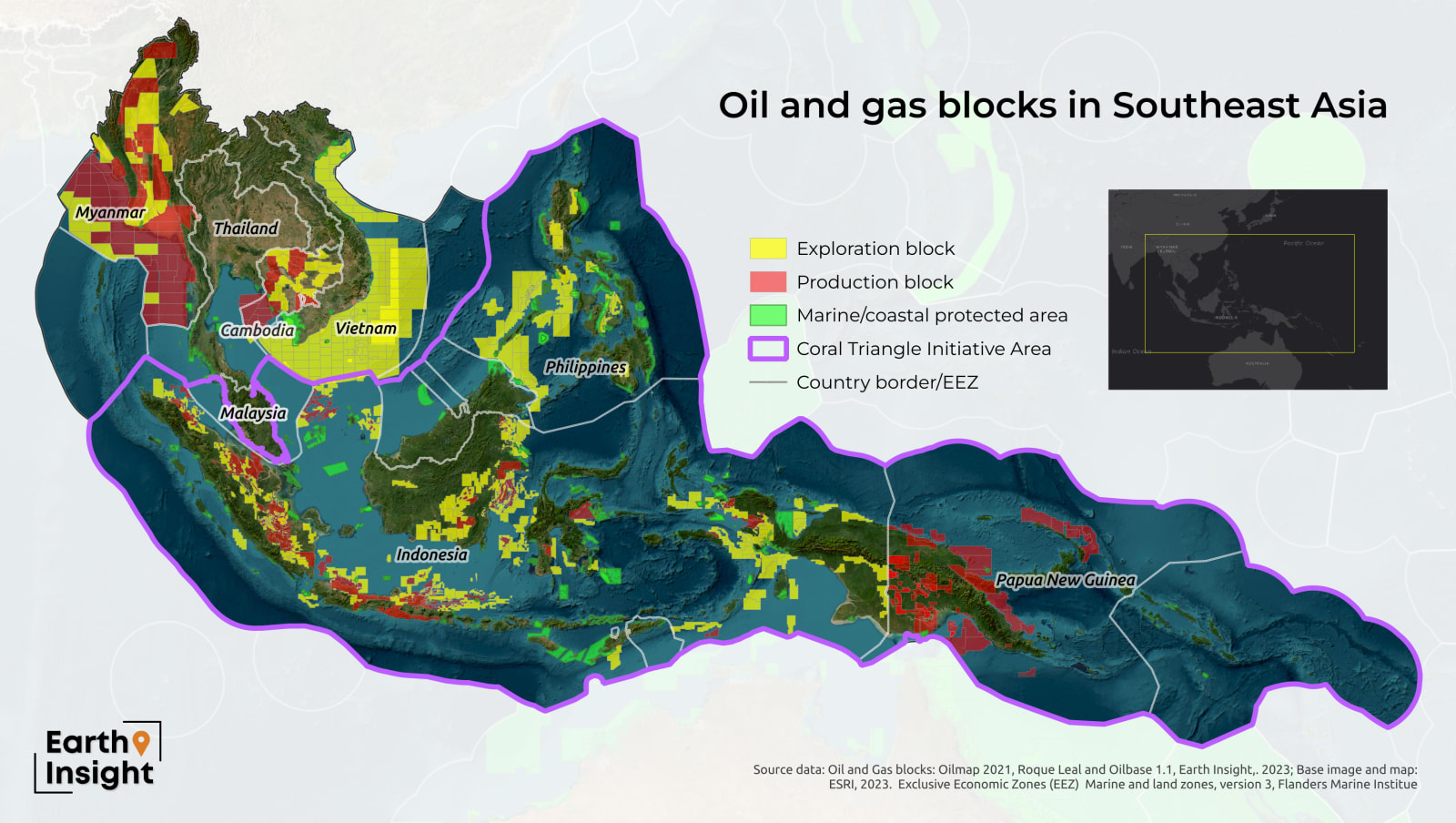

Analysis by Earth InSight, which maps “threats to people, nature and climate”, shows that more than half of the reef ecosystems in the Coral Triangle area are under oil and gas production or exploration blocks. More than 300 such blocks have been mapped in the area.

“Consistently, the Department of Energy via policy, has not wavered on aspirations to have additional discoveries, exploration, development and production beyond Malampaya,” DOE’s Mr Rino Abad said.

But, he admitted that geo-political realities, especially around the South China Sea and in the country’s restive south, would make offshore development more difficult.

Mr Reynolds said that these upstream resources remained difficult to operationalise, region-wide.

“You need to more realistically assess what projects are likely and possible. But there’s certainly a need to worry about the climate impacts of these developments,” he added.

The approval of new gas fields in the coming years would have detrimental impacts on regional climate change targets, Mr Reynolds said. Much of Southeast Asia’s gas reserves contain high amounts of carbon dioxide that when released and processed would contribute to global warming.

LINGERING LOCAL IMPACTS

More than seven months on from the oil spill off Oriental Mindoro, a fishing ban remains in waters around Pola. The livelihoods of those affected have been decimated.

Oil still pervades the mangrove forests and beaches, “like asphalt on a highway”, according to a local fisherman.

About 75 kilometres of shoreline were directly affected, according to authorities. The vast majority of oil onboard the vessel had already leaked out by the time syphoning efforts began in late May.

Concerns about income and health remain, especially among fisherfolk. And the spill was just another death knell for the local environment.

“Our waters in Mindoro were very beautiful. Its deep blue waters showed how clean it was. Our fishing grounds were different in the past, and we lived in abundance,” said Mr Orly Maranan, a fisherman from Naujan.

“You can see for yourselves how it is now. We are unable to catch anything. There’s really nothing. Zero. It’s lifeless,” he said.

Authorities have declared the emergency over and the clean-up operations a success. Yet, it is not clear how long the impacts will last.

“There’s no such thing as 100 per cent instantly clean,” Commander Geronimo Tuvilla, of the Philippine Coast Guard in Southern Tagalog, told CNA.

Legal recourse is still being pursued by Pola’s Mayor Cruz on behalf of her community. She wants the ship’s owner – RDC Reield Marine Services – to compensate for damages.

More broadly, she also wants bans on oil and chemical tankers from passing through the conservation corridor, or at the very least, much more thorough scrutiny and inspections of such vessels and their operators.

Pamalakaya, a national federation of fishermen’s organisations in the Philippines, supports such measures and would not oppose making the Verde Island Passage a protected marine area, as long as fishing is not totally banned in the area.

“We think there is a threat of destruction to the Verde Island Passage. When tankers that are full of oil sink, then it really is very alarming,” said Mr Fernando Hicap, the group’s chairman.

The MT Princess Empress was one of 11 oil spill incidents in the first eight months of 2023 in the Southern Tagalog and Bicol Region alone. It is the most number of annual incidents recorded this century in the area.

Mr Abad from DOE said that the companies transporting LNG and other chemicals have the experience, funds and personnel to lower the risk of future incidents.

“Accidents happen every now and then. Of course, it’s not absolute that you can actually avoid them 100 per cent,” he said.

The lingering impacts and the chance of a repeat disaster are tough truths to swallow in Pola.

Given the earmarked expansion of fossil-gas infrastructure around Batangas, Mayor Cruz may not get all the restrictions and recourse that she and her community are after.

“We are just trying to make the best of what happened because our environment has already been destroyed,” she said.

“I have no problems with development. But responsibility must always accompany development.”

Additional reporting by Aiah Fernandez.

Source

CNA