search the site

Case study: Crew injury after fall of heavy object

Case study: Crew injury after fall of heavy object

Lifting operation had not been formally risk assessed and a lifting plan had not been produced

by The Editorial Team August 18, 2021 in AccidentsThe ship in berth, showing accident site and wind turbine sections for loading / Credit: UK MAIB

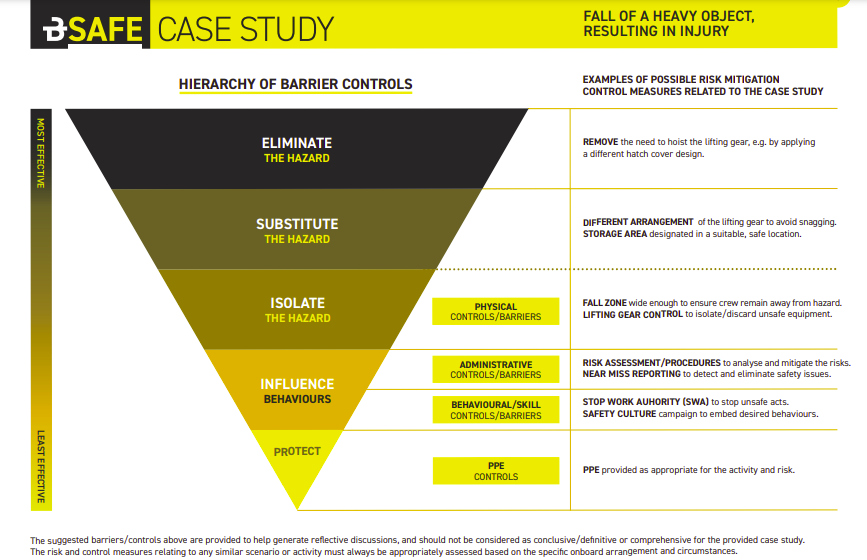

Two crew members on a general cargo ship were injured when a suspended load fell and struck them. The suspended load were wire rope legs and shackles used to move the ship’s hatch covers (“the lifting gear”), which fell because the hoist parted after one of the shackles became wedged at the storage location. As part of its BSafe campaign, Britannia Club shared lessons learned from the incident.

The incident

A 11,000 GT general cargo ship built in 2018, was to load a cargo of wind turbine tower sections. The deck crew, supervised by the chief officer (C/O), began to prepare the ship for cargo loading. This work was halted in the afternoon due to adverse wind conditions, but was scheduled to recommence later in the evening when the weather was expected to improve. At 2100 the weather had improved. The C/O conducted a safety briefing and took up the position as supervisor, accompanied by the bosun. The ship’s working lights were turned on, illuminating the area where the crew were to work.

Following the safety briefing, one of the ABs used the ship’s forward crane to remove the cargo hold ventilation duct space cover, so that the lifting gear could be retrieved. Two other A/Bs then entered the ventilation duct space and attached the first of two hatch cover lifting gear sets to the crane’s hook using a fibre sling. Both A/Bs then climbed out of the space and stood close to the hatch edge ready to guide the load and free any snags as it was lifted.

RELATEDNEWS

Russia opens criminal investigation into Black Sea tanker spill

TSB Canada investigation: Crew fall overboard after workboat struck by mooring line

There was no designated storage space for the lifting gear on board. The lifting gear had been stowed on wooden pallets positioned on top of the ventilation duct coamings in the ventilation duct space ever since delivery by the shipbuilder. The lifting gear was made up of two slinging sets; each set weighed 0.6t and consisted of two 17m long, 52-millimetre (mm) diameter, wire rope legs joined together with a master link. Each wire leg had a shackle attached to an eye at the lower end.

Using a radio, the C/O instructed the A/B to control the crane to commence lifting. After the load had been lifted about 2-3 metres, the gear snagged. The C/O ordered the crane driver to stop hauling and the two A/Bs on deck freed the snag by hand. With the two A/Bs remaining close to the edge of the hatch the C/O ordered the crane driver to start heaving again.

Shortly after the lifting operation recommenced, a shackle at the lower end of the load became snagged on a ventilation trunk coaming. The C/O immediately instructed the crane driver to stop, but at the same time the fibre sling parted and the lifting gear fell to the deck, striking both A/Bs.

GET THE SAFETY4SEA IN YOUR INBOX!

One of the A/Bs suffered a severe head injury while the other suffered a minor hand injury. Other crew members administered first aid and raised the alarm. Ambulance paramedics were soon on the scene and treated both A/Bs before transferring them to a local hospital. The A/B who had suffered the serious head injury was later transferred to a dedicated neurological injury unit, before eventually being repatriated.

After the accident, the parted sling and five other similar slings from the ship were examined at an expert testing centre. The report of these tests stated that all six slings would have failed a visual inspection as they were soiled and had illegible identification markings.

Lessons learned

The following lessons learned are based on the official investigation report:

- The deck preparations had been delayed by weather and there was pressure to prepare the ship for the cargo loading.

- The operation was not stopped by any of the involved crew when the A/Bs positioned themselves close to the suspended load.

- The ship’s SMS did not contain a risk assessment or a procedure for the stowage and handling of the hatch cover lifting gear, nor any guidance for the conduct of a lifting plan and the identification of fall zones.

- With no procedure to follow, the crew had adopted their own method of carrying out the lifting operation. The crew had experienced similar snagging events on previous occasions. When these had occurred, the deck crew had manually freed the gear after the crane had stopped hauling. No Near Miss report or corrective actions followed.

- The ship had not been built with a dedicated storage area for the hatch cover lifting gear. In result, the crew had devised a local storage arrangement which might have appeared appropriate, however had a significant number of potential snagging hazards. This storage arrangement had not been subject to a formal risk assessment.

- The load fell because the synthetic fibre sling used to lift it parted under tension. Although the sling’s nominal SWL was more than twice the weight of the load being lifted, the sling was in a poor condition and should have been discarded.